If you grew up a Chinese Restaurant Kid, you’d know that there are always two menus in the restaurant- a white menu and the real menu. My dad sold the restaurant long before I started making memories, but while we bonded (read: capitalised on child labour) over the pleating of dumplings, the folding of spring rolls, scrubbing of bones and slicing of meats, he would always tell me about the rubbish on the white menus.

“We have to make everything so greasy, big, sweet and fluorescent for white people to buy it.”

The way he tells it, while he made proper dumplings for the Chinese customers, he’d have to make what he learned to be dim sims for white people and the more full of meat scraps (read: fat) it was, the more people enjoyed it. Spring rolls were predominantly filled with corn starch in stir-fried cabbage water. Lemon chicken had honey, sugar and yellow dye in it. Sweet and sour pork was inedible to his palate. To train mine, not only did he get me to season and balance all the dishes we cooked together, but he would always hold back a portion of any sauce and show me how he would season it for white people. I’d twist my tiny face up, spit it out and call it disgusting. Boy, was he proud.

While my dad would joke that he was tricking white people into eating rubbish, I knew it was his coping mechanism in dealing with the fact that he couldn’t sell real Cantonese food to the general public. Not only was he rejected professionally and socially by white Australians, his food was being rejected and that’s all he had left. Anglicised Chinese food wasn’t born out of trickery, it was born out of survival. The thing about immigration is that even if you were a school teacher, an engineer or a surgeon back in your country, your degree isn’t recognised here. Unfortunately, the most educated people I have met are either serving me food or driving me from point A to point B so they can pay for night school.

Back in the 80s when suburban Chinese restaurants were one per suburb, serving facsimiles of your cuisine to white people was the smart way to support your family. With your limited resources, you could get by with learning numbers, yes, no, ok, and opening and closing a cash drawer (which was always just a box with a cheap lock on it from a hardware store). Sure, there were always rumours that you were serving stray cats and dogs, but people seemed to trust you if you made the same fucking dishes for them all the time. While Aussie-Chinese food isn’t as lurid as American-Chinese food, to this day, it is still classified as a form of greasy take out. Mate, it’s only greasy because you wanted it that way.

Culturally, Chinese people are raised to respect (and fear) their elders (and superiors). We are not born free, we aren’t meant to dream, and we are not given choices in how we want to live our lives. We are necessary products to aid in the survival of the previous generation (mainly because there is no pension in Hong Kong). We are taught to occupy as little space as possible and keep our opinions to ourselves. This is why when white Australia demanded Anglicised Chinese food, we provided it. We are occupying your space and we are here to serve you so we are allowed to continue living. We’ll do anything, just don’t send us back to the threat of Communist rule.

Recently, a friend of mine who also works in the food media space asked me why Chinese people don’t put the super traditional dishes on the menu and you have to ask for it. The reason is, it’s not a popular item and you either have the ingredients or you don’t. Specific people ask for these dishes on rare occasions. To put it on the menu would mean food wastage and also a waste of ingredients that are a pain in the arse to source (read: bring back home in suitcases every time a family member goes to China and pray customs lets it through). There is also the hangover of having to placate white Australians and not look like we are serving cats and dogs. Those who ran restaurants 20-30 years ago still live in fear that it can all be taken away.

As more Chinese people emigrated to Australia, there was a demand for real Chinese food. There are less bastardised Cantonese restaurants and there are even those serving traditional Uyghur, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, Hunan and Shandong cuisine. I smile when I see single-item restaurants here that are common all over China. While it has taken this long to mould the palates of white Australians, I don’t think these restaurants could have been established without a need for it. And that is to say, aside from the few converted, regional Chinese restaurants with only one menu are only growing in popularity because Chinese people are now outnumbering white Aussies in Australia and there is a fetishisation over authenticity in the food community.

If only my dad had the energy to open a restaurant today.

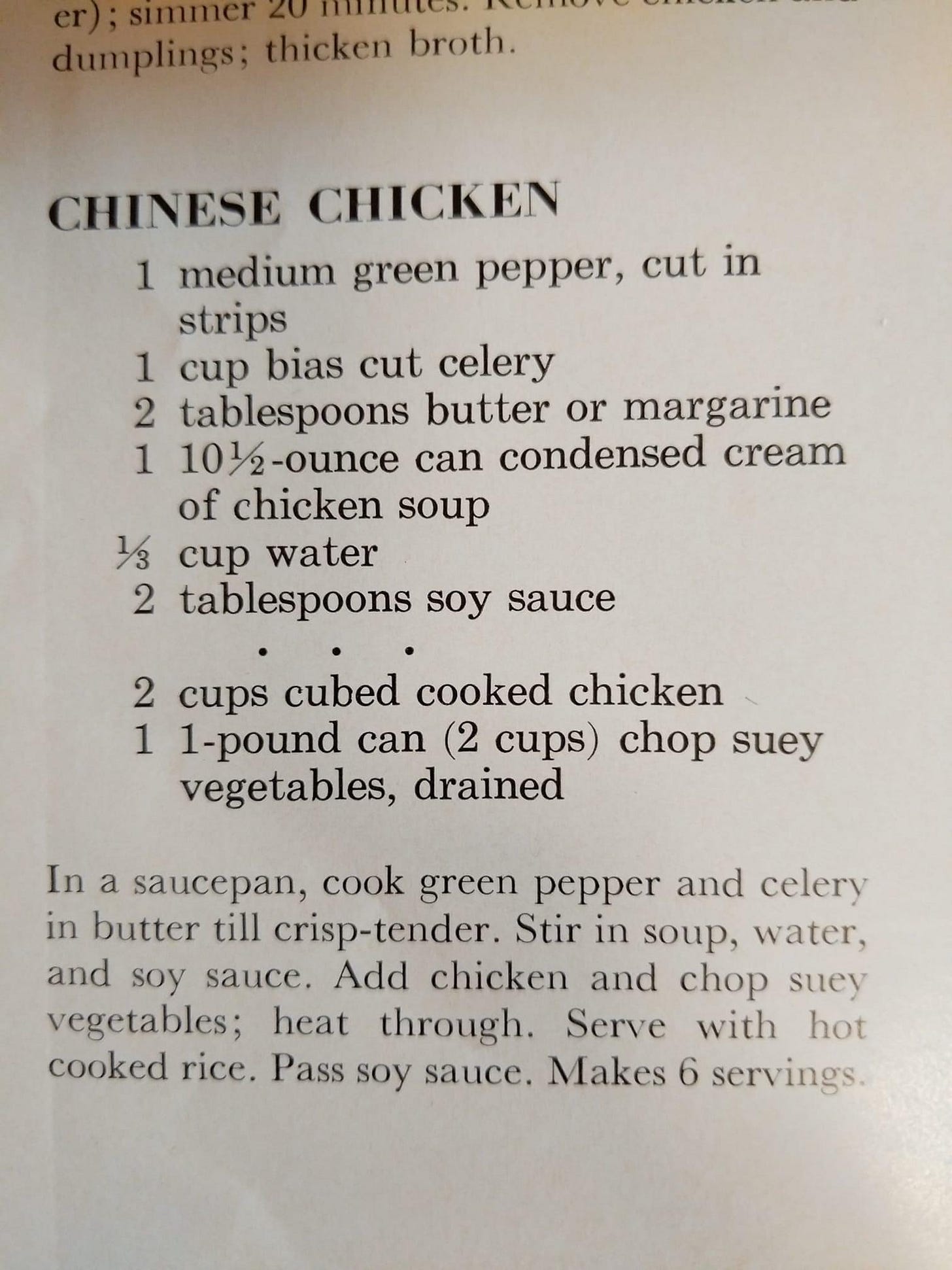

I’ll leave you with the recipe for Chinese Chicken from the 1968 Better Homes and Gardens Casserole cookbook:

What I’m reading:

One of the most influential books I read growing up was Please Kill Me by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain and I only just realised there is a music journalism website with the same name run by McCain and McNeil. I’ve fallen in the rabbit hole and there is no getting out. Let me die here in peace.

What I’m watching:

The latest season of Fargo. Am I loving it? No. Am I hating it? Also no. A lot rides on the last few episodes.

What I’m eating:

A lot of Sydney Rock oysters, it seems. It doesn’t matter where I go for dinner, I can’t say no to the Sydney Rocks. Again, there is no saving me. Let me die here in peace.

Want to tell your friend how you were also a Chinese Restaurant Kid?

Were you the Chinese Restaurant Kid?

Love the article and your observations! Reminds me of the time in the early 80s when stopping in Mansfield on the way home from a day trip to the snow (imagine what seeing an Asian at Mt Buller would have been like for the whities) for dinner around 6pm. The Chinese restaurant at the edge of town would always get a decent crowd to pickup fried dimmies, flourescent pork with pineapple for take away and greasy fried rice to eat in the car on way home. But when my friends, all caucasians except for me, stopped by, I peeked into the kitchen and spoke to them in Cantonese and asked if we could have some "family" food, not the stuff on the menu blackboard. 15 minutes later, our group got some delicious home cooking and we always ate in the out of way table.

Towards the end of that ski season, we noticed that there were more diners eating in the restaurant and we almost couldn't get a table. And to my delight, I saw them all eating "family" food that wasn't on the menu.

This also happened often in the 1970s as we travelled around the state. Whether it was Portland, Bendigo, or Mildura, dropping in to the local Chinese restaurant, I always remembered by father chatting with the owner and seeing if we could just get some family food off-menu. Some of the best Chinese food I've had was from those days.

It's so good that 30-40 years on we have some amazing Chinese food in Melbourne. Let's hope Covid hasn't been too unkind to them.